My daughter placed a packet of papers on my hospital tray and said, “Just sign for your treatment.” I reached for the pen, but the nurse paused, reread the first page one more time, and gently asked me to wait. “Let’s confirm a few details first,” she whispered, sliding the papers back. A staff member came in to explain everything clearly, and the room went quiet. That’s when I realized my signature wasn’t routine. It mattered.

The hospital room had that peculiar brightness that never matched the hour. Even with the blinds half-closed, the fluorescent lights made everything look too clean, too sharp, like the world had been scrubbed until nothing soft survived. My hip throbbed in a deep, mechanical way, as if someone had bolted a stubborn part into me and my body was still negotiating with it. The pain itself was honest, but the medication made the rest of reality feel like a rumor.

I floated in and out of sleep, the kind that isn’t really sleep at all. More like drifting along the edge of consciousness where time folds in on itself. The monitor beeped with patient indifference. A cart squeaked in the hallway. Somewhere down the corridor a phone rang and rang, as if nobody wanted to admit it belonged to them.

When the door opened, I knew it before I saw anyone. The air shifted, a small current moving across my skin, and my eyelids fluttered like they were too heavy to lift. A shadow crossed the floor, clean and confident.

“Mom,” my daughter’s voice said, bright in that practiced way, like she was smiling before she finished the word. “There you are.”

Vivien stepped in holding a folder against her chest the way people carry something important. Her hair was perfectly smoothed back, not a strand out of place, and her makeup was done as if the hospital were a restaurant and she didn’t want to be caught looking ordinary. She leaned over my bed and kissed the side of my forehead, careful not to smudge her lipstick. The kiss was light, more like punctuation than affection.

“You look good,” she said softly, and there was a thin edge of urgency underneath it, like she needed my body to cooperate on a schedule. Her eyes flicked to the monitor, then back to my face, as if my condition were a series of checkboxes.

I tried to respond, but my mouth was dry and my tongue felt thick. The medication made my thoughts slow, as if they had to wade through syrup before they could become words. I blinked up at her and managed a small nod.

Vivien pulled the tray table closer, the plastic wheels rolling with a quiet rattle. She set the folder down and flipped it open with the confidence of someone who already knew what every page said. The paper rustled, crisp and impatient.

“Okay,” she said, tapping the first sheet with a polished nail. “I need you to sign these. It’s just routine paperwork for your treatment. Billing needs it before they can process everything, and I don’t want any delays.”

A pen appeared in her hand and then in mine. She placed it between my fingers and guided my grip, the way you guide a child’s hand when you’re teaching them to write their name for the first time. Her touch was firm, not caring.

I stared at the paper. The words blurred and swam. I could see paragraphs, blocks of text, a signature line, but they refused to settle into meaning. My brain tried to focus and couldn’t, like a camera lens stuck between sharp and fog.

“It’s fine,” Vivien said quickly, watching my face. “You don’t have to read the whole thing. It’s standard. Just sign where I highlighted.”

She slid the page closer. A yellow strip of highlighter glowed near the bottom. A signature line. My name printed in neat type above it, as if it had been waiting for me.

This was the part where a good mother doesn’t make things difficult. This was the part where you trust your child, because the alternative is too painful to hold in your hands. For sixty-two years, trusting my children had been the default setting of my heart.

I lifted the pen. The tip hovered above the line.

The door opened again.

“Mrs. Hartwell?” a woman’s voice called, brisk but not unkind. “I’m just going to check your vitals.”

Teresa came in with a rolling cart, her scrubs a soft navy that made her eyes look sharper. She was in her fifties, maybe older, with the calm confidence of someone who had spent years meeting people at their most vulnerable. Her hair was pulled back in a no-nonsense bun. A badge clipped to her pocket flashed when it caught the light.

“Hi, Vivien,” Teresa said, polite but neutral. “How are we doing?”

Vivien’s smile widened, just a little too bright. “We’re fine. I’m just helping Mom with her paperwork.”

Teresa nodded and came closer, looping the blood pressure cuff around my arm. Her hands were efficient. She didn’t fill the room with chatter. She worked in focused quiet, reading the monitor, checking my IV, adjusting a line with practiced eyes.

As she leaned over to smooth the blanket near my waist, her gaze flicked to the papers on the tray table. It wasn’t dramatic. Just a glance that happened on instinct, like noticing a spill on the floor.

Then her eyes narrowed.

I watched her expression change, subtle but unmistakable. Teresa leaned closer to the page, as if she were confirming a detail. For a second she didn’t move, and the quiet in the room sharpened until I could feel it in my teeth.

Vivien noticed it too.

“Is something wrong?” Vivien asked, still smiling.

Teresa didn’t answer right away. She adjusted my IV again, but her attention stayed on the paper.

“Mrs. Hartwell,” she said softly, not to Vivien, but to me, “can you tell me what you’re signing?”

I blinked, confused. My mouth opened and nothing came out fast enough. My mind kept slipping, like a tire on wet pavement.

Vivien laughed lightly. “It’s just billing forms,” she said, like Teresa was being silly. “She had surgery. You know how it is.”

Teresa’s eyes lifted to Vivien’s face. They were calm, but something in them hardened, like a door clicking shut without noise.

“Ma’am,” Teresa said evenly, “can I see that paperwork for a moment?”

Vivien’s smile faltered, then returned, tighter. “Why? It’s personal.”

Teresa didn’t move away. She didn’t raise her voice. She simply held out her hand.

“It’s hospital policy,” she said. “If a patient is signing anything while medicated, we confirm consent and comprehension. Just for safety.”

Vivien’s jaw flexed. “This isn’t hospital paperwork.”

Teresa’s hand stayed out. “Then it doesn’t need to be signed in a hospital bed.”

The pen trembled in my fingers. The tray table suddenly felt like the center of the universe, like everything that mattered was trapped on that rectangle of plastic and paper. Vivien reached toward the documents as if to pull them closer.

Teresa stepped forward without thinking, her body instinctively placing itself between the tray table and Vivien’s hand.

“Let’s pause,” Teresa said quietly. “Mrs. Hartwell, I’m going to hold onto this for a moment. We’ll confirm a few details first.”

She slid the papers away from me with gentle firmness, like she was removing something sharp from a child’s reach. Then she pressed the call button on the wall.

The sound was soft, almost polite, but the energy in the room shifted completely.

Vivien’s voice rose, not loud, but fast. “Teresa, you don’t need to do that. This is a family matter. You’re overreacting.”

Teresa didn’t look at her. She looked at me, her face calm but intent.

“Mrs. Hartwell,” she said, lower now, “these aren’t medical forms.”

My mouth went dry all over again. I tried to sit up, but the movement pulled pain through my hip and I gasped. The pain cut through the fog, bright and immediate.

“What?” I whispered.

Vivien’s eyes flashed. “Mom, don’t listen to her. You’re confused.”

Teresa’s hand rested lightly on my shoulder. “You’re not confused,” she said. “You’re medicated. That’s different.”

The door opened and a charge nurse stepped in, followed by a hospital security officer in a dark uniform. He was tall, broad-shouldered, with gray at his temples and a calm face that looked like it had learned to stay steady when other people spun. He didn’t swagger. He didn’t rush. He simply arrived like a boundary.

Teresa handed him the folder without ceremony.

“Please review this,” she said.

Vivien stiffened. “This is ridiculous.”

The officer flipped open the folder and scanned the first page. He didn’t skim like someone checking a menu. He read like someone weighing consequences.

His eyebrows lifted slightly.

He looked up at Vivien. “Ma’am,” he said, voice controlled, “this appears to be a durable power of attorney document.”

Vivien recovered fast. “It’s just in case,” she said. “My mother is recovering. She needs help with her affairs.”

The officer turned another page. Then another. His mouth became a straight line.

“There’s language here regarding transfer of financial authority,” he said. “And medical decision-making authority.”

Vivien’s eyes flicked to me, sharp as a hook. “Mom, tell them. Tell them you want me to handle things.”

My heart pounded. Words like authority and transfer and decision-making swirled in my head like birds startled from a tree. I tried to hold onto one clear thought and couldn’t.

Teresa stepped closer to the officer and spoke quietly, but I heard her.

“She’s post-op,” Teresa said. “Still under anesthesia effects. She should not be signing anything like this.”

The officer’s gaze stayed on Vivien. “Ma’am,” he said, “attempting to have a medicated patient sign a power of attorney is a serious issue.”

Vivien’s voice sharpened. “Are you accusing me of something? I’m her daughter.”

The charge nurse spoke then, calm but firm. “We’re not accusing you,” she said. “We’re safeguarding the patient.”

Teresa’s hand squeezed my shoulder once, not hard. Just enough to remind me I wasn’t alone.

The officer nodded toward the doorway. “Ma’am, you need to step out,” he said. “We’ll escort you.”

Vivien’s polished expression cracked. For a second, something raw and furious showed through, and then she tried to cover it with that wounded look she had perfected over a lifetime.

“You can’t do this,” she snapped. “This is my family.”

Teresa’s voice stayed low. “This is our patient,” she said. “And she deserves protection.”

Vivien turned to me, desperation flashing across her face, then quickly replaced by innocence.

“Mom,” she said, voice trembling just enough to sound sincere, “tell them I’m here to help you. Tell them they’re making you scared.”

I stared at her, trying to reconcile the daughter I raised with the woman standing at the foot of my bed with paperwork like a weapon she had disguised as routine. My mouth opened. No words came. The fog in my head was no longer soothing. It was dangerous.

The officer stepped forward. “Ma’am,” he repeated, “please.”

Vivien lifted her chin with indignation. “Fine,” she said. “I’ll leave. But you’re all going to hear from my lawyer.”

She grabbed her purse with a jerky movement and stormed out. The officer followed. The room exhaled, but I didn’t. My lungs felt like they’d forgotten how.

When the door clicked shut, Teresa pulled a chair close and sat beside my bed.

“Mrs. Hartwell,” she said gently, “stay with me. Can you look at me?”

I did. My vision swam slightly, but her face stayed steady in front of mine.

“Tell me your full name,” she said.

“Opel,” I whispered. “Opel Hartwell.”

“Good,” Teresa said. “Do you know where you are?”

“The hospital,” I said, swallowing. “Fairfax.”

Teresa nodded, eyes softening. “Okay. You’re doing fine.”

The charge nurse spoke quietly, like the room might break if voices got too loud. “We’re going to note this in your chart,” she said. “And we’ll restrict visitors until you tell us otherwise.”

I stared at Teresa as my mind finally caught up enough to understand what almost happened. My signature wasn’t routine. It mattered. It was a key.

“She… she tried to,” I started, my voice shaking.

Teresa didn’t sugarcoat it. “If you had signed those,” she said, “she could have had legal control over your finances and your medical decisions.”

My chest tightened like a fist closing. The thought didn’t feel like a thought. It felt like the floor dropping.

“She said they were billing forms,” I whispered.

“That’s why I stopped it,” Teresa said. “You didn’t deserve that.”

Shock has its own dryness. It empties you out. I stared at the tray table, now empty except for a plastic cup and a folded napkin, and I kept seeing the yellow highlight like a warning flare. I kept feeling the pen in my fingers.

A memory rose up suddenly, uninvited. Vivien at eight years old, running into the house with scraped knees, crying because a boy on the playground pushed her. I had cleaned her wound and told her she was safe. I had meant it.

Now I lay in a hospital bed realizing safety is not guaranteed by love.

“Can I call someone?” I asked, voice trembling like it didn’t belong to me.

Teresa nodded. “Yes,” she said. “Who do you want to call?”

“My son,” I whispered. “Davis.”

Teresa helped me find my phone on the bedside table, then adjusted my pillows so I could sit up more comfortably. Her hands were efficient, but her kindness was deliberate, as if she knew how much it mattered that someone stayed, that someone didn’t treat this like a passing inconvenience.

When I dialed Davis’s number, my fingers shook so badly I almost dropped the phone. The call rang twice, then he answered, breathless like he had been moving when it rang.

“Mom?” he said immediately. “How’d it go? Are you okay?”

I tried to speak and my voice broke. “Davis,” I whispered. “Something happened.”

The line went quiet for half a second, the kind of quiet that means the world has shifted and someone is bracing.

“What happened?” he asked, voice sharper now, more focused.

I told him slowly, the way you tell someone bad news when you’re afraid if you say it too fast it will become real. Papers. Routine. Highlighted line. Teresa. Security. Power of attorney. The words sounded like they belonged to someone else’s life.

Davis didn’t speak for a long moment. I could hear his breathing on the other end, controlled, like he was keeping his temper leashed.

“Mom,” he said finally, voice low, “I’m coming.”

“You don’t have to,” I whispered, though my heart begged him to anyway. “It’s far.”

“I’m coming,” he repeated, and there was no debate in his tone. “I’m booking a flight right now. You’re not dealing with this alone.”

Tears slid down my cheeks, quiet and steady. They weren’t dramatic. They were the kind that come when a dam finally admits it’s been holding back too much.

Teresa handed me a tissue without a word.

“Did the hospital call the police?” Davis asked.

“They’re documenting it,” I said. “Teresa said I should report it.”

“Good,” Davis said. “Report it. Don’t let her talk you out of it.”

His words stabbed me with guilt even as they steadied me. Even now, a part of me wanted to defend Vivien out of reflex, because I had trained myself for decades to soften her consequences.

“Mom,” Davis said, softer, “I love you. Stay awake if you can. I’ll call you back with details.”

When I hung up, my hands trembled as if the phone were still vibrating. Teresa leaned in slightly.

“Your son sounds like a good one,” she said.

“He is,” I whispered. Then, because the truth needed somewhere to go, I added, “I didn’t know I needed him like this.”

Teresa’s eyes softened. “Sometimes you don’t know until you do,” she said.

Later that evening, after the floor settled into its nighttime rhythm, Denise the social worker came in. She wore a cardigan over her blouse and carried a folder the way people carry facts they don’t want to drop. Her expression had the careful seriousness of someone who has learned that sympathy without action is useless.

“Mrs. Hartwell,” she said, pulling up a chair, “I’m sorry this happened to you. I want to talk about next steps.”

My body felt heavy, but my mind was clearer now. The medication had eased enough for reality to land fully. I nodded.

Denise spoke calmly, outlining options. A police report. A call to Adult Protective Services. Legal consultation to protect assets. Changes to bank accounts. Restricting visitors. Updating medical directives. The words sounded clinical, but underneath them was the truth: you need walls when the person who knows where the doors are decides to break in.

“I feel embarrassed,” I admitted quietly. “Like I should have seen it.”

Denise shook her head. “You trusted your daughter,” she said. “That’s not embarrassing. That’s human. What matters is what you do now.”

After Denise left, I lay in the quiet and let my mind drift backward, not because I wanted to live in the past, but because the past finally made a certain kind of sense. It was like turning on a light and seeing the mess you’d been stepping around for years.

I wasn’t a woman who lived wildly. I wasn’t dramatic. I worked, I saved, I kept my house clean, I made sure the lights were paid and the lawn didn’t turn into a jungle. Leonard and I built a steady life the American way, slowly, with long commutes and careful budgeting and the kind of exhaustion that comes from responsibility.

For thirty-one years I worked as an office manager at a construction company in Northern Virginia. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was steady. Phones, schedules, invoices, payroll, crews that depended on me to make sure their checks didn’t get “lost in the system.” I learned how to keep men with heavy equipment and heavy opinions moving in the same direction.

Leonard worked with his hands. He loved coming home to a quiet house and a hot meal. We weren’t rich, but we were secure. We were the kind of couple that planned for retirement with a binder on the shelf and a financial adviser we trusted, a woman named Mrs. Kendrick who had a calm voice and a talent for making the future feel manageable.

Then Leonard got sick.

Pancreatic cancer doesn’t negotiate. It arrives like an unwelcome guest and then refuses to leave. The first year we fought. The second year we adjusted. The third year we learned what it meant to love someone through the slow stripping away of strength.

When he died, the world didn’t end. It just went quiet in a new way. The silence was so loud it filled rooms. For months I would reach for my phone to tell him something small, some stupid detail, and then remember there was no one on the other end.

After the funeral, I sold our larger house and moved into a smaller place closer to town. A one-story home with a little porch and a living room that still smelled faintly like Leonard’s aftershave for months, until time diluted it into memory. It was manageable. It was mine.

I had two children. Davis, my son, lived in North Carolina with his wife Cheryl and their three boys. Every Sunday morning without fail my phone would ring, and it would be Davis asking about my week, telling me about the boys’ baseball games, complaining about the humid summers near Raleigh, making plans for the next visit.

He wasn’t perfect, but he was present. He showed up.

Vivien lived twenty minutes away. Close enough that distance was never an excuse. Somehow she was still always far.

For most of her life, I made excuses for her. When she was young and selfish, I told myself she was independent. When she grew up and started asking for money, I told myself she was going through a rough patch. When she stopped calling unless she needed something, I told myself she was busy, and I shouldn’t be the kind of mother who guilted her for having her own life.

After Leonard died, the requests increased. Credit card debt. Car repairs. Rent money when she fell behind. A “small loan” to “get her back on her feet.” Each time she promised it would be the last time. Each time I believed her because the alternative was admitting my child had learned how to use my love like a lever.

Over nine years, I gave her nearly forty thousand dollars.

Not all at once. Not in a dramatic scene. In a series of decisions made in kitchens and parking lots and late-night phone calls where she cried just enough to make my heart override my head. Sometimes she would pay back fifty dollars, a hundred, just enough to keep the illusion alive that it was a temporary situation and not a pattern.

Vivien didn’t come to visit just to visit. There was always a reason, always something she needed. When she did show up, she would glance around my home like she was appraising it, running her fingers along the furniture Leonard and I had picked out together, asking questions that felt too pointed.

“Have you thought about selling this place?” she asked once, smiling lightly. “It’s a lot of house for one person. You could get good money for it.”

“I like my house,” I told her. “I’m not ready to move.”

She gave me that sweet smile, the one that always arrived before a request.

“I’m just thinking about your future, Mom,” she said. “You won’t be able to take care of yourself forever.”

At the time, I told myself she was being caring in her own clumsy way. Now I understood she had been taking measurements. She had been building a plan, and I had been building excuses for her.

Six months before my surgery, the questions became sharper.

Vivien started showing up without calling first, something she had never done before. She would knock on my door on a Saturday afternoon, let herself in before I could answer, and sit down at my kitchen table like she had been invited.

At first I was almost happy. I thought maybe she was finally making an effort. I made coffee. I offered cookies. I asked about her week. She smiled, nodded, gave me just enough attention to keep my hope alive.

Then she turned it, clean and quick.

“Mom, I’ve been thinking about your finances,” she said one afternoon, stirring her coffee like this was casual conversation. “Do you have everything organized? Your accounts, your retirement, your investments.”

I tried to laugh. “Why are you worried about that?”

“I’m not worried,” she said, still smiling. “I’m just being responsible. You know, in case something happens.”

In case something happens. The phrase sounded like concern until you heard it too many times, until it started sounding like a countdown.

She wanted to know which bank I used. She wanted to know how much I kept in savings. She asked about my pension, my Social Security, the life insurance payout from Leonard’s death. Each question felt like a small intrusion, but I kept telling myself she was being mature.

Then she asked about my will.

“Have you updated it since Dad passed?” she said. “You really should. You don’t want the state getting involved if something happens to you.”

“My will is fine,” I told her. “I updated it after your father died. Everything is split evenly between you and Davis.”

She nodded slowly, but I could see she wasn’t satisfied. Her eyes moved like she was recalculating.

A few weeks later, she came with a new idea.

She thought I should move in with her.

“It would be easier,” she said. “For everyone. You wouldn’t be alone. I could help take care of you. You could sell this place and put the money somewhere safe. I could manage it so you don’t have to deal with bills and taxes and all that stress.”

I looked at her sitting in my living room, in the house Leonard and I had shared for years, and I felt something cold settle in my stomach. She wasn’t offering to take care of me. She was offering to take over.

“I’m not ready for that,” I said. “I’m healthy. I can manage my own life.”

Her face tightened. “You’re sixty-two, Mom. You’re not going to be independent forever.”

“I’m independent now,” I said, and my voice surprised me with its firmness. “And I’m staying here.”

She didn’t argue, not directly. But something shifted after that conversation. The warmth she had been pretending to show me disappeared. When she visited after that, it felt less like a daughter checking on her mother and more like someone inspecting a property they intended to claim.

Then my hip finally gave out in a way I couldn’t ignore.

Years of walking on concrete floors at work had worn the joint down, and the pain had gotten bad enough that I couldn’t pretend it was “just getting older.” My doctor showed me the X-ray and shook his head gently.

“We can keep treating symptoms,” he said, “or we can fix the problem.”

Hip replacement surgery. Early October. A plan, a date, a process.

When I told Vivien, her whole attitude changed, like someone flipped a switch.

Suddenly she was attentive. Suddenly she was calling me. Suddenly she was offering to drive me to pre-op appointments. She said she would be there during intake. She said she would stay with me when I woke up.

It was such a convincing performance that I let my doubt go quiet. Pain has a way of making you accept whatever help is offered, even when your instincts whisper that help can come with a hook.

The morning of surgery, she held my hand in the pre-op area and told me everything would be fine. She smiled. For a moment, I let myself believe I had been wrong about her, that maybe those uncomfortable conversations had been clumsy concern.

I went into that operating room thinking my daughter had finally come back to me.

I woke up and found out she had been waiting for the moment I couldn’t fight back.

That was the truth Teresa had pulled into the light with one simple question.

Can you tell me what you’re signing?

It was such a small interruption. It saved my life anyway.

The night after Vivien was removed from my room, I didn’t sleep much. Every time I drifted, my mind yanked me awake with the image of the yellow highlight and the pen hovering above the line. I kept hearing the security officer’s voice, calm and controlled, saying durable power of attorney, as if he were reading a weather report.

By morning, the fog in my head had lifted enough for anger to arrive.

Not wild anger. Not screaming anger. The kind that sits in your chest like a stone and makes you realize you have been soft in all the wrong places for too long.

The police came to take my statement that afternoon. A detective with patient eyes asked me to start from the beginning. I told him about the questions, the visits, the pressure, the paper.

He didn’t look shocked. That was its own kind of horror.

“This happens more than people think,” he said. “Especially when someone assumes they’re entitled.”

Entitled. The word fit like a key in a lock.

Davis arrived the next day.

The moment he walked into my room, I felt my chest loosen. He looked tired, hair slightly unkempt, backpack slung over one shoulder like he had been moving fast. His eyes went straight to my face, scanning, checking, making sure I was still me.

“Hey, Mom,” he said softly. His voice shook just a little. “I’m here.”

I tried to smile. “You didn’t have to…”

“Yes,” he said, cutting me off gently. “I did.”

He leaned down and kissed my forehead, but his touch didn’t feel like performance. It felt like presence. The difference was so sharp it made me want to cry again.

Teresa came in a few minutes later and gave Davis a quick overview. She spoke plainly, not dramatizing anything. I watched Davis’s face change as he listened, the calm draining out of him and being replaced by something harder.

When Teresa left, Davis sat in the chair beside my bed and stared at the wall for a moment, jaw clenched.

“I want to call her,” he said quietly.

I swallowed. “Davis…”

“I’m not going to yell,” he said. “I’m not going to threaten. I just want to hear her try to explain it.”

I shook my head slowly. “Not yet,” I whispered. “Please.”

Davis’s eyes softened. “Okay,” he said. “We’ll do it your way. But we’re not letting this go.”

That afternoon, Denise returned with a list of attorneys who specialized in elder protection. The name Mrs. Fontaine stood out because Denise underlined it twice.

“She’s strong,” Denise said. “She doesn’t let families talk their way out of facts.”

Mrs. Fontaine came to the hospital the following morning. Tailored suit, neat hair, calm presence that made the room feel less chaotic. She didn’t treat me like a fragile old woman. She treated me like a client with rights.

She listened to the story without interrupting. When I finished, she nodded once.

“We lock this down,” she said.

She outlined immediate steps. Freeze credit. Change passwords. Add two-factor authentication. Update beneficiaries. Restrict medical access. Create a no-contact order. Document every attempt at communication.

“Most people don’t want to do this to their own child,” she said, as if reading my mind. “That hesitation is what people like your daughter count on.”

I flinched at people like your daughter. Hearing it said out loud made it real in a way my heart still resisted. But it also steadied me.

Davis stayed, and the hospital became a strange bubble of safety. Nurses came and went. Physical therapists helped me stand with a walker and take slow steps down the corridor while the pain cut through me like a bright line.

Vivien did not return in person during those days, but she tried in other ways.

A voicemail appeared on my phone. Her voice was soft, wounded, trembly in a way designed to sound sincere.

“Mom, I don’t know what happened,” she said. “They treated me like a criminal. I was trying to help you. Please call me. Please don’t let Davis poison you against me.”

I listened once, then handed the phone to Davis.

Davis’s face went hard. “Poison you,” he repeated, voice flat. “She tried to steal your life with paperwork.”

I should have felt purely angry. Instead I felt the old guilt rise, the one that always told me I was responsible for fixing everyone. I hated that it still lived in me.

Mrs. Fontaine told me not to respond to voicemails. Not to argue. Not to explain. Not to negotiate.

“Clarity,” she said. “Short sentences. Hard boundaries. No openings.”

It sounded cold until I remembered the pen in my hand, guided by Vivien like I was a child.

If I didn’t build walls, she would keep coming through.

I was discharged eight days after surgery. Davis insisted on wheeling me out even though I wanted to walk.

“Let me,” he said. “Just this once.”

Outside, the air was sharp and cold. The parking lot smelled like exhaust and winter. Cars moved past the hospital entrance like nothing had happened, like the world didn’t care that my daughter had almost taken everything.

On the drive home, Northern Virginia looked the same as it always did. The same exits. The same strip malls. The same traffic crawling on I-495 like a tired animal. Holiday decorations hung half-heartedly from light poles along Route 50.

Everything outside looked normal.

Inside me, nothing was.

At home, Davis set up a recovery station in my living room. Extra pillows. Water. A medication schedule. A notebook where he wrote down every instruction from the discharge papers like he didn’t trust memory to keep me safe.

“I’m fine,” I protested, though I didn’t mean it.

“I know you’re fine,” Davis said, not looking up from his notebook. “I’m still doing it.”

The first night home, I woke at 2:13 a.m. with my heart pounding, sure I had heard something outside. I lay there listening. The house creaked softly, settling the way old houses do. The heater clicked on. A car passed down the street.

Nothing happened.

But my body stayed braced as if danger were crouched on the porch.

In the morning, Davis found me sitting at the kitchen table with a mug of tea, staring at nothing.

“Nightmares?” he asked gently.

“Not exactly,” I admitted. “Just… fear.”

Davis sat across from me and took a breath as if he were choosing his words carefully.

“Mom,” he said, “what she tried to do was about control. The way we beat control is structure. Steps. Systems. Not feelings.”

“I don’t know if I can be that cold,” I whispered.

“You don’t have to be cold,” Davis said. “You just have to be clear.”

Clear. The word stayed with me.

Later that week, Mrs. Kendrick, my financial adviser, met us at her office near Tysons Corner. The building smelled like coffee and carpet cleaner and expensive cologne. The lobby had a holiday wreath that looked like it had been installed by someone who didn’t celebrate anything, just followed policy.

Mrs. Kendrick shook my hand warmly and looked me in the eyes. “Opel,” she said, voice gentle, “I’m sorry.”

We went over accounts and beneficiaries. We changed passwords. We added extra layers of security. We wrote notes in my file that no changes could be made without in-person confirmation and a code phrase.

As Mrs. Kendrick printed the new documents, she looked at me carefully. “It happens more than people think,” she said quietly. “Especially when someone believes they’re entitled to what you built.”

On the way home, Davis drove in silence. The sky was gray and heavy. Cars crawled along the highway.

When we got home, my phone buzzed. Unknown number.

Davis glanced at it. “Don’t answer.”

I stared at the screen as it rang. The old part of me wanted to pick up, to soothe, to make things okay. The new part of me remembered the yellow highlight.

I let it go to voicemail.

A message arrived seconds later.

Mom, it’s me. Please. I need to talk to you.

My fingers trembled. I felt the pull like gravity.

Davis’s voice was calm, but it carried steel. “Mom, this is where clarity matters.”

I typed one sentence, exactly as Mrs. Fontaine instructed.

You are not permitted to contact me. Any further contact will be reported.

My thumb hovered over send. My heart screamed that I was being cruel. Then I remembered the pen hovering above the line in the hospital.

I hit send.

The house didn’t explode. The world didn’t end. No dramatic shift in the air.

But inside my chest, something settled into place, like a bone sliding back into alignment after being out for too long.

That afternoon, while I practiced my physical therapy exercises in the living room, my hip aching in that steady, honest way, I realized something I hadn’t allowed myself to realize before.

I had spent years protecting Vivien from the consequences of her choices.

Now I was finally protecting myself.

The landline rang the next morning. I barely used it, but it still came with my internet plan. Davis picked up.

“Hello.”

His shoulders tightened in a single beat, then his voice went cold.

“Who is this?”

He didn’t put it on speaker, but I heard the fast voice on the other end, sharp and urgent, the way people talk when they believe volume can turn into power.

Davis responded in short, nailed-down sentences.

“No. She’s recovering. She’s not speaking with you.”

A pause. The voice sharpened.

“Leave it,” Davis said into the phone. “You were removed as an approved contact. You’re not welcome here. If you come to this house, we will call the police.”

He set the receiver down slowly, like he refused to give the person on the other end the satisfaction of pulling him into their storm.

“What did she say?” I asked, even though I already knew.

“She said she was only trying to help,” he told me. “And she said I’m poisoning you against her.”

A dry laugh slipped out of me, not joyful, just bitterly familiar. “She always needs a villain,” I said. “If it isn’t her, it has to be someone else.”

An officer came by that afternoon, polite and professional. His name tag read RODRIGUEZ. He confirmed I wanted to file additional information and move forward with a temporary protective order.

“Ma’am,” he said, “if she shows up and refuses to leave, call 911. Don’t negotiate. Don’t open the door.”

I nodded, stomach cold. I hated needing those instructions. I hated hearing them about my child.

After he left, Davis adjusted the front-door camera, shifting the angle so the porch was fully visible. He worked quietly.

“You know how to do that?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Cheryl made me learn,” he said. “Three boys. You learn everything if it keeps the house safe.”

That evening Mrs. Fontaine emailed the protective order paperwork. I read each line and felt it close a door I’d left open for years because I’d believed family love was a master key.

Davis handed me a pen.

“This time,” he said softly, “you’re signing to protect yourself, not because someone guided your hand.”

My fingers still trembled, but I read my own name on the page and felt the weight of it. Opel Hartwell. A person with the right to decide.

I signed.

Two days later, the doorbell rang.

My body froze. My heart punched hard against my ribs. Davis wiped his hands on a towel and checked the camera.

His face changed.

“Mom,” he said low, “it’s her.”

Cold went through me, but I didn’t scream. I didn’t fall apart. I stood slowly, holding the chair for balance, and walked into the living room. On the small hallway screen, Vivien stood on my porch in a cream-colored coat, hair perfect, a gift bag in her hand like this was a normal visit. She stared straight at the camera, knowing we were watching.

Davis didn’t open the door. He spoke through the intercom.

“Leave,” he said. “Now.”

Vivien smiled and lifted the bag.

“Call me the villain if you want,” she said. “But she’s my mother.”

Davis answered without raising his volume. “She is not available. You are not permitted here. Leave.”

Vivien tilted her head and made her face look wounded, the way she always did when she needed to flip the script.

“Mom,” she called, eyes fixed on the camera. “Please. I just want to talk.”

I stepped closer so Davis knew I was ready, then spoke into the intercom. My voice sounded rough, but it held.

“Vivien,” I said, “you need to leave.”

She went quiet for a beat, as if she hadn’t expected me to speak.

“Mom, don’t do this,” she said quickly. “You’re not thinking straight. You’re on pain meds. Davis is…”

“Stop,” I said. The word came out clean. “I am thinking straight. Leave.”

Vivien stared at the camera for a long moment, then the smile dropped. Her face went flat, real, and cold.

“Fine,” she said. “You’ll regret this.”

Davis pressed a button. “I’m calling the police.”

Vivien turned, walked fast to her car, tossed the gift bag into the backseat like it meant nothing, and drove off.

Only when her taillights disappeared did I realize my hands were shaking. Davis turned toward me, his eyes full of concern.

“You okay?” he asked.

I took a slow breath in, then out. “I’m okay,” I said. And the frightening thing was, I meant it.

The protective order was approved two days later. Mrs. Fontaine called with the news.

“She cannot contact you,” she said. “She cannot come to your home. She cannot come to your treatment locations. If she violates it, you call police immediately.”

I didn’t feel triumphant. I didn’t feel vindicated. I felt empty, like a room after you’ve cleared out old furniture.

That night I lay in bed and stared at Leonard’s photo on my dresser. In it, he wore a flannel shirt and smiled gently in front of his old pickup. I stood beside him, my hair darker then, my hand on his shoulder.

I whispered, not sure if I was speaking to him or to myself.

“I tried.”

A week later Sergeant Bowman called with an update. His voice stayed even, but the information made my stomach clamp down.

“Mrs. Hartwell,” he said, “we obtained a warrant for her devices. There are searches and drafts indicating planning. She researched how to obtain power of attorney from an incapacitated parent. She looked up property transfer procedures. There are messages suggesting intent to move funds quickly.”

Davis sat beside me, his hand tightening into a fist.

“Is she going to be charged?” Davis asked.

“Attempted fraud and exploitation,” Bowman replied. “The DA will determine exact charges, but the case is being taken seriously.”

After the call, Davis stepped outside for air. I knew he needed space so his anger wouldn’t detonate inside my home. I stayed at the table and listened to the clock tick, like time itself was teaching me.

Time wouldn’t return the years I’d talked myself into denial, but it could still save the years I had left.

A few days later, a plain white envelope appeared in my mailbox. No return address. Just my name and Vivien’s handwriting.

My heart kicked hard, but I didn’t rip it open. I carried it inside, set it on the kitchen table, and stared at it like it was a blade wrapped in paper.

Davis walked in, saw it, and immediately knew. “From her?”

I nodded.

“Don’t open it,” he said, quick and protective.

But I shook my head. “I need to know how scared I still am,” I told him. “If I can’t open an envelope, that means she still has a string tied to me.”

I opened it slowly. Inside was a single-page letter on lightly scented paper, as if she believed perfume could soften a lie.

Mom,

I never meant for any of this to happen. That nurse humiliated me. Davis came in and turned everyone against me. I only wanted to make sure things were handled if something went wrong. You’ve always been stubborn and you refuse to see that you need help. I’m your daughter, and I’m the one who lives nearby. I’m the one who can take care of you. Please don’t let strangers and lawyers ruin our family. I love you. Call me. We can fix this.

Love,

Vivien

I read it and felt tears rise, not from tenderness, but from recognition. She was still rewriting the story so she stayed good. Not one sentence admitted what she’d actually done. No apology for lying. Just humiliation, blame, and my stubbornness.

Davis looked at me.

“You see it,” he said, not to pile on, but to keep me steady.

“I do,” I whispered.

I folded the letter and placed it in the file box with the rest of the paperwork. Evidence, not memory.

My body healed in inches. Walker to cane. Cane to careful steps up my front porch with my hand on the railing. Each improvement felt like I was taking back a portion of my life someone had tried to steal with ink.

Davis stayed five weeks, just like he promised. He did the little things Leonard used to do. Replaced a light bulb. Fixed a sagging cabinet hinge. Checked the oil in my mower. He didn’t announce it. He just restored peace to the house, one small task at a time.

One evening, while we watched an old movie on PBS, Davis spoke without looking at me.

“You know,” he said, voice tired, “I warned you a few times.”

“I know,” I said.

“I’m not saying it to blame you,” he added. “It just hurt. Watching her drain you and you still protecting her.”

My chest tightened, but I didn’t dodge it this time.

“I thought being a mother meant enduring,” I said. “I thought if I let go, it meant I failed.”

“Letting go isn’t failure,” he said. “Letting go is saving yourself.”

When the court date came, I didn’t want to go. I didn’t want to see Vivien in that setting. I didn’t want to be the mother on one side and the daughter on the other, the whole thing reduced to a case name and a file number. I wanted quiet.

Mrs. Fontaine was blunt.

“If you don’t show up,” she said, “other people will write the story. And you’ll hate their version.”

So I went.

Davis drove me to the Fairfax County courthouse on a cold morning. The building was pale stone, and the American flag out front snapped and softened with the wind like breathing. I walked slowly through security, heard the metal detector chirp, heard shoes echo on the polished floor.

The courtroom wasn’t like the movies. Smaller. Less theatrical. But heavier, because it was real. People whispered, shuffled documents, checked phones, like this was just another Tuesday.

Vivien arrived with a lawyer. She wore a dark coat, her hair still styled, but her confidence looked thinner. When she saw me, something flashed across her face, then she looked away quickly.

Her attorney talked about a misunderstanding, about family stress, about confusion. Mrs. Fontaine didn’t perform. She didn’t dramatize. She simply stated facts.

“This was planning,” she said. “The documents were prepared in advance. The timing was selected. The patient was medicated. The intent was to obtain control.”

The judge looked at Vivien with a tired kind of seriousness.

“Ma’am,” he said, “do you understand the gravity of what you attempted?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” Vivien replied, but her eyes didn’t hold his.

Real life didn’t end in handcuffs. It ended in conditions and paperwork. A deal. A reduced charge with probation. A permanent no-contact order. And the part that mattered most to my future, she signed away any claim to my estate.

Part of me wanted harsher consequences. Another part of me was too tired to spend a year inside courtrooms. I wanted peace more than revenge.

Afterward, I stepped out into the cold wind and felt it slap my face into clarity. Davis stood close, his hand hovering behind my back like he was ready to catch me if I swayed.

Vivien walked past us with her lawyer. She paused, turned toward me, eyes red but dry.

“Mom,” she said softly, and for once her voice didn’t sound sweet. It sounded stripped down. “Are you happy now?”

I stared at her and realized I couldn’t answer the way I used to. I couldn’t say I’m sorry. I couldn’t smooth it over. I couldn’t pretend love was enough to rewrite reality.

“I’m safe now,” I said. “That’s what I wanted.”

Vivien blinked like she’d been hit. A short, humorless laugh escaped her, and she turned away, moving down the courthouse steps as if she needed to outrun my sentence.

When Davis went back to North Carolina, the house turned quiet again. I thought loneliness might swallow me whole.

It didn’t.

It was a different kind of quiet now, the quiet of a home with its doors locked properly. The quiet of a woman who had stopped waiting to be treated right and started insisting on it.

I still called Davis every Sunday. I still heard three boys fighting over a game and then shouting, “Hi Grandma!” into the phone like I was a celebrity. I laughed, and the laughter didn’t taste bitter anymore.

One day Teresa called me, and I was surprised she even remembered my name.

“Opel,” she said brightly, “how’s the hip?”

“Better,” I told her. “I’m walking with a cane now.”

“Good,” she said. Then her voice softened. “Listen, I’ve been thinking about you. You handled that day with more strength than you realize.”

I hesitated. “I still feel shaken sometimes,” I admitted. “Like I’m waiting for the next shoe to drop.”

“That’s normal,” Teresa said. “Your nervous system took a shock. But you know what helps? Turning it into purpose.”

She told me about a volunteer program at the senior center in Fairfax. Helping people with Medicare forms, scam calls, and paperwork traps. She kept it simple, not sentimental.

“You have lived experience,” she said. “That’s powerful. People listen when it’s real.”

A few weeks later, I walked into the senior center. It wasn’t fancy, just a community building that smelled like cheap coffee and cookies. One room had bingo. Another had tai chi. A bulletin board was covered in flyers: smartphone basics, walking group, insurance workshop.

A coordinator named Carol greeted me with a warm handshake.

“Opel,” she said, “we’re glad you’re here. A lot of folks get overwhelmed. They get scared. They need someone patient.”

“I can be patient,” I said. “And I can be honest.”

My first sit-down was with an older man whose hands trembled as he opened a text thread. Someone claiming to be his grandson had asked for money, urgent, pleading. He didn’t know if it was real.

“I feel stupid,” he whispered.

“No,” I told him. “You feel human. Scammers count on that.”

I didn’t lecture. I slowed him down. I showed him how to verify, how to call the family number he already had, how not to let urgency bully him into a mistake.

When I went home that day, my leg was tired but my heart felt lighter. My pain wasn’t just mine. It was a story other people were living quietly, ashamed, and sometimes without a Teresa walking in at the right moment.

The weeks moved on. The Virginia sky changed. The last leaves fell. The cold deepened. My house was still my house, but it wasn’t a place of waiting anymore.

It was a place where I lived.

Near the end of November, Davis called.

“Mom,” he said, voice lighter, “we’re coming up for Thanksgiving. Cheryl already booked it. The boys are excited.”

“I’ll make stuffing,” I said. “And pecan pie.”

When they arrived, my home filled with noise so fast it felt like sunlight. The boys charged in, kicked off shoes, shouted, argued, and then fought over who got to hug me first. Cheryl held me longer than usual, her eyes wet.

“I’m so sorry,” she whispered. “I wish we’d been closer.”

“You’re here now,” I said. “That’s what matters.”

Thanksgiving dinner wasn’t perfect. The turkey ran a little dry. One of the boys spilled water. I felt a familiar ache when I looked at the chair Leonard used to fill. But it was real. It wasn’t performance.

After the meal, Davis stepped outside with me onto the back porch. The air was cold enough to turn our breath into fog. A neighbor had already hung Christmas lights, red and green blinking across the fence line.

Davis watched me for a moment, then said quietly, “You know… I used to be afraid you’d never choose yourself. You always chose her, no matter what she did.”

My throat tightened. “I was wrong,” I said. “I thought giving more meant loving more. But sometimes giving more just feeds something bad.”

Davis nodded. “Now you know,” he said.

“I don’t want to hate her,” I admitted. “But I can’t pretend.”

“You don’t have to hate,” Davis said. “You just have to stop handing her the keys.”

That night, I lay in bed listening to my house full of people and felt something I hadn’t felt in a long time.

Peace.

Not because everything was healed, but because it was finally true.

In the morning I woke early, made coffee, and stared out the window at the thin frost on the grass. The boys were still asleep. The house was quiet in the rare way only a full house can be quiet.

My phone buzzed with an unknown number.

My heart jumped, but I didn’t panic. I looked at the screen and set the phone down. I listened to the hum of the refrigerator, the faint creak of the house, the gentle rhythm of a life that had survived.

I chose not to open the door.

I chose peace.

And in that moment I understood what it had taken me a lifetime to learn. Love doesn’t mean giving someone permission to destroy you. Sometimes love is simply standing up and saying no, without shaking from guilt.

…

News

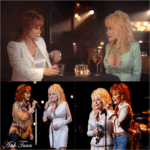

“I Still Miss Him”: Dolly Parton Breaks Down Mid Song as Reba McEntire Joins Her for Heart Shattering Tribute to Late Husband Carl Dean.

“I Still Miss Him”: Dolly Parton Breaks Down Mid Song as Reba McEntire Joins Her for Heart Shattering Tribute to…

This guitar carried my soul on its strings when no one knew my name…

In the electric silence that follows a singer’s last note, when the world holds its breath in anticipation of what’s…

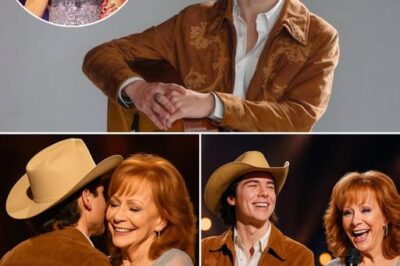

The Voice reveals 4 returning coaches for season 28 including Niall Horan and Reba McEntire

The duo will be joined by fellow show alums Michael Bublé and Snoop Dogg. Nial Horan and Reba McEntire on…

Reba McEntire: “Drag Queens Don’t Belong Around Our Kids”

Reba McEntire Sparks Controversy with Statement on Drag Queens and Children. Country music legend Reba McEntire has found herself at…

Reba, Miranda Lambert, & Lainey Wilson Debut Powerful New Song, “Trailblazer,” At The ACM Awards

“Trailblazer” Is A New Song That Celebrates The Influential Women Of Country Music’s Past And Present Reba McEntire, Miranda Lambert, and Lainey…

Jennifer Aniston made a surprise appearance with a dazed expression and an unresolved…

Jennifer Aniston is no stranger to the public eye. For decades, she’s been one of the most beloved faces in…

End of content

No more pages to load